What makes a person the same person over time? A British philosopher, Nigel Warburton, introduced me to personal identity via the “Ship of Theseus” thought experiment.

Now, let’s embark on a journey of contemplation. Imagine Theseus’s ship, lost at sea; its hull is the only remnant. A new vessel is painstakingly crafted from the salvaged wood, bearing the same name as the original. But is this new ship truly the same as the old one? I invite you to delve into this question, explore how you perceive personal identity in this context, and consider whether you can draw any parallels to your life experiences.

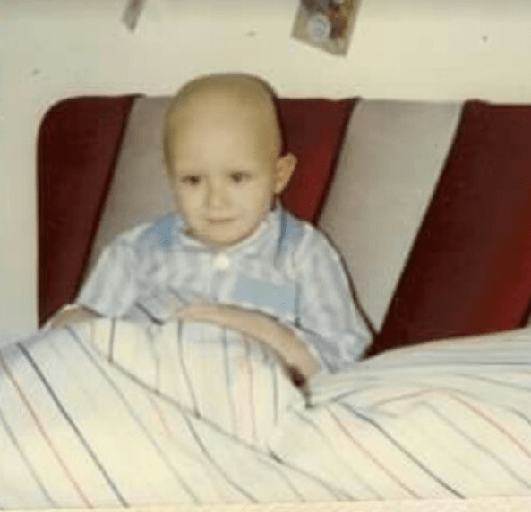

As we grapple with the ship’s enigma, let’s delve into a more profound question: Can a person remain the same over time? This is not just an abstract philosophical puzzle; it’s a question that each of us, in our unique ways, has to confront. Reflecting on my journey, I arrive at a resolute conclusion: I am the same person today as the four-year-old child who courageously faced a Medulloblastoma, a brain tumour. This personal insight, born from the depths of my experiences, underscores the profound depth and complexity of individual identity.

In philosophy, ‘personal identity’ refers to what makes a person the same person over time. It’s important to note that ‘personal identity’ is distinct from political ‘identity’ (which encompasses cultural and ethnic origins, sexual preferences, and so on). In my writing, I use ‘personal identity’ and ‘professional identity’ interchangeably in chapter five-Social Enterprise. Both these aspects, my personal and professional identity, contribute to defining the person I am, including the child diagnosed with Medulloblastoma in 1987.

I cannot say with certainty. Medical records were received after the time of writing. However, a small percentage of medulloblastomas related to gene changes can be passed down through families (Cancer.gov). I am 90 per cent sure my medulloblastoma was genetic. The person I am today was preconditioned before birth.

Philosophy, however, is not written with childhood medulloblastoma survivors in mind. Therefore, when philosophers argue their conclusions supported by true premises, they do so based on undeniably correct objectivity. My argument here is subjective, remaining so until the completion of chapter six: Do I consider myself disabled today? In philosophical terminology, my conclusion, my subjective conclusion, is that I am the same person through time because of a traumatic event—a childhood medulloblastoma diagnosis.

Hopefully, the reader is beginning to grasp who I am. Ponder this question: Can the person I am today with, 36 years of navigating a society, a society based on institutional objectivity, have subjective happiness/ well-being? Shawn Achor, writing in The Happiness Advantage, points out that ‘the most enjoyable part of an activity is the anticipation’. What if the anticipation of a career change, system change, or recognition never comes? How is happiness/well-being affected?

The remainder of this chapter focuses on my childhood medulloblastoma diagnosis and the side effects of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and stroke. As mentioned above, I have not received my medical records at the time of writing. I write this chapter from memory using published documentation to provide legitimacy to my degrading memory.

In the UK, 52 children are diagnosed with medulloblastoma each year. In 1987, I was unlucky enough to be one of the 52. Medulloblastoma is the most common childhood malignant (high-grade) children’s brain tumour. Malignant means the tumour is cancerous. A high-grade malignant medulloblastoma means it is a miracle I am here to write this book 36 years after the diagnosis.

On social media, I was asked what type and sub-type of medulloblastoma I had. Honestly, that information evades me. Once I receive my medical history, I shall insert that information into the chapter notes.

As a child, my favourite cartoon was ‘He-Man and the Masters of the Universe’. I had all of the figures, including Orko. Orko is the comedic character who comes across as a clumsy oaf. The silly little sorcerer provided many laugh-out-loud moments for the three-year-old I was. On reflection, when my parents started to call me Orko. Alarm bells should have gone off. No parent wants to call their child a clumsy oaf. No parent wants to find out their child has a medulloblastoma. The reality is that children who become clumsy oafs over a short period could have a brain tumour. If you see this change in your child, I urge readers to go to the doctor and demand a referral for a scan.

Cancer Research UK lists the following as symptoms of a medulloblastoma: headaches, sickness, double vision, standing or sitting unsupported, loss of appetite, and behavioural changes.

Double vision and standing or sitting unsupported. I dub this Orko syndrome. If your child has Orko Syndrome, get to the doctor for a referral for a scan, and don’t take no for an answer. I don’t think I ever lost my appetite. My issue was that I could not keep any food down concerning the behavioural changes. I spent most of my pre-diagnosis days in a dark room to stop the headaches. That is a massive behavioural change for a child who just turned four.

Above, I mentioned that only 52 children in the UK will be diagnosed with a medulloblastoma each year. Therefore, at least today, I hold no animosity towards the general practitioners (GPs) who misdiagnosed my condition as jealousy of my younger brother and play-acting. Fiercely, I condemn the GPs, who in their right mind think a four-year-old is voluntarily making himself vomit to the point of death out of jealousy of a younger sibling? The thought alone is outrageous. Outrageous, disgraceful, bordering on eccentric.

Eccentricity is supported by objectivity. Society supports institutional objectivity, and social norms reinforce it. Therefore, I cannot condemn GPs because they are part of a system of governance built on institutional objectivity. As a social science graduate, I am tasked with understanding society, not asking for a system change. Sorry, I cannot do that. At this point, the readers should understand I am the same person today, not because of the medulloblastoma. I am the same person today because of society’s inability to support adults who had brain tumours as children.

Cognitive awareness of the months/years directly following my medulloblastoma diagnosis is absent. Perhaps it is for the best, as it allowed me to move past that experience quickly. By the time I was eighteen, I wanted nothing to do with my medulloblastoma diagnosis. That is getting ahead of the story. Not having my medical records on hand prevents me from providing you, the reader, with the technical details of my brain tumour. A friend on social media had a non-malignant brain tumour the size of a cream egg. Sorry, @Tumourkilller, my malignant brain tumour dwarfed your non-malignant brain tumour. I am a survivor. I have bragging rights. I am attempting to tell the reader that not having my medical records on hand is a blessing, making writing this chapter more authentic. I hope the authenticity I give the reader will be returned with legitimacy.

Objectively, surviving a high-grade malignant medulloblastoma is more impressive than surviving a non-malignant brain tumour the size of a cream egg. That’s how an institutional system with objective evidence would view it. However, I am too altruistic and understand the importance of viewing the situation holistically to take that view. @Tumourkiller is authentically telling his story to empower himself and inform his viewers. Tumour killer (Ryan) deserves legitimacy. Legitimacy, I argue, provides the speaker with dignity. What the GPs did, what society did, removed my parent’s dignity. Only 52 children are diagnosed with high-grade malignant medulloblastoma each year in the UK. I understand the objective view of the GP. I also understand that place and past dependency matter. The GP would have lacked the knowledge and understanding to diagnose a child with high-grade malignant medulloblastoma. Understand, yes; forgive, no. What the GP did was remove any legitimacy my parents had. Therefore removing their dignity. That objectively is a breach of human rights. My views on human rights in Scotland were covered in chapter one.

In 1987, I was diagnosed with high-grade malignant medulloblastoma—a childhood brain tumour.

“Medulloblastoma is likely to grow quickly and can spread to other areas of the brain and spinal cord. Around 30 out of 100 children (around 30%) have medulloblastoma that has spread when they are first diagnosed.”

(Cancer Research UK, n/a)

I was one of the 70 per cent of diagnoses where the cancer had not spread to other parts of my body—no secondary cancer – the name given to cancer that spreads. Additionally, to date no recurrence. I do not know the type of chemotherapy or dosages I received. I also don’t know anything about the radiotherapy I was given. I remember having to be held still in a mask attached to a table—readers who have watched The Man in the Iron Mask, like that, only shackled to a table with radiation being fired at me. Today, my spinal cord is shunted due to the radiotherapy. Though better to be a few inches shorter than biologically expected than dead.

I cannot be too sure about the side effects of the chemotherapy. Today, from what I know about neurodivergent individuals, I think my brain works similarly. However, that could be due to removing the tumour damaging surrounding parts of the brain, not the chemotherapy. I believe I had some form of learning disability in primary school caused by the chemotherapy. More realistically, however, is a sensory loss – hearing and sight were an issue as far back as the late 80s. I refused to acknowledge it. The education system, NHS, social workers, and even my parents failed to see it.

As far as the stroke is concerned, I have a slight speech impediment, cannot walk in a straight line, and have constant double vision. Today, I am considering asking for a symbol cane. To stop the double vision, I have to blind my left eye, and as I am sure you can imagine, walking with only one eye while not being able to walk in a straight line has its difficulties. A symbol cane would inform the public that I have sight issues.

In the fictional case of Howie vs. Scotland, the judge had no choice but to find in my favour. Scotland failed Howie by not delivering on getting it right for every child (GIRFEC). Scotland could not protect my human rights—mainly rehabilitation and the right to live in the community. Scotland failed to transition Howie from GIRFEC to Getting It Right for Everyone (GIRFE).