Society is structured to grow the gross domestic product (GDP). However, allocating available resources to grow GPD results in the most vulnerable citizens becoming an afterthought. The social enterprise/ framework Iain and I designed after completing our MSc in social innovation empowers citizens and communities by focusing on the diversity, inclusion, and belonging model.

It is of utmost urgency that we address the critical issue of empowering disadvantaged citizens in Scotland. The evidence is stark: Disabled individuals confront substantial inequalities and are at a higher risk of living in poverty. This is a policy concern and a societal crisis that demands immediate action. I am deeply concerned that the Scottish Government may lack the capacity and resources to enact the required changes. The time for action is now.

While I acknowledge that the A-LEAF framework may not be a panacea for all the Scottish government’s challenges, I am confident it could be a significant step towards a more inclusive and equitable society for disabled people. This is not just a proposal. It’s a beacon of hope, a potential catalyst for positive change. Given the opportunity, this framework could not only enhance the well-being of countless disabled citizens in Scotland, but it could also transform their lives, offering them a brighter future. Let’s unite to envision this potential, understanding the profound impact it could have on the lives of our fellow citizens.

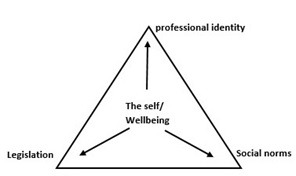

The A-LEAF framework I propose is more than just an abstract idea. It is a practical solution rooted in my personal experiences and the expertise of my graduate colleague, Iain. With over thirty years of collective experience, A-LEAF is based on the belief that citizens’ well-being is enhanced when they have a personal and professional identity, when social policy supports their right to live in the community, and when social norms allow them to do so. This is not just a theoretical concept but a tangible framework that can be implemented to bring about real change, instilling confidence in its practicality and effectiveness.

The A-LEAF framework is essentially the Iron Triangle on Sustainable Steroids. It aligns seamlessly with the Scottish Government’s well-being/ circular economy policy and advocates for a new fourth social enterprise sector. This framework is designed to bolster green growth and foster co-production in the three existing sectors – third, private, and public. Its implementation could significantly enhance the Scottish Government’s initiatives and policies, leading to a more inclusive and equitable society.

Network theory is the idea that organisations within society collaborate to make society function. Each node does its job or the job it has a competitive advantage in—it can complete the job better and generate more profit than any other node/organisation. The A-LEAF framework enhances the network for the common good by placing it in a strategic action field. Every action field network node works towards the well-being/circular economy.

In academic social enterprise theory, there are three typologies of social entrepreneurship. Schumpeter inspires social engineering thinkers to believe that a newer, more effective social system is designed to replace existing systems when systems are ill-suited to address significant social needs. As a social innovation graduate, a citizen of Scotland and someone disabled by the medical model, I have sympathy for this thought pattern. However, such political philosophy/ social enterprise typology needs to be revised. Such philosophy has no place in contemporary society.

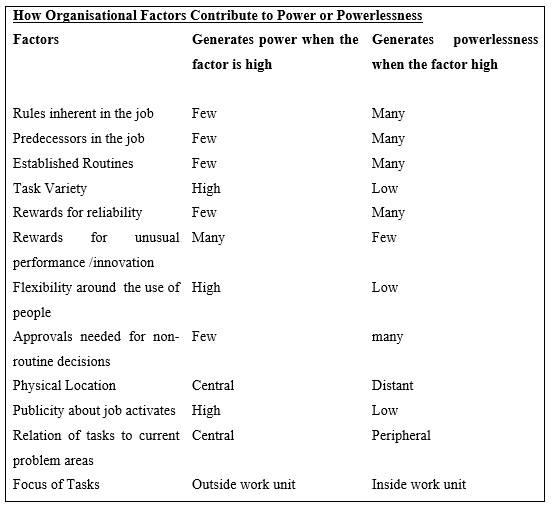

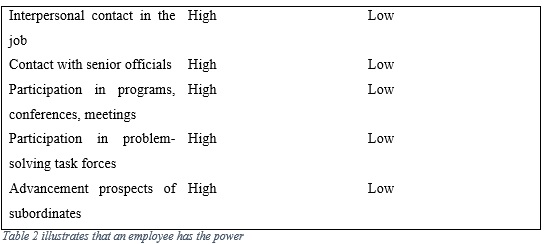

The typology operating in society presently is social bricoleur. Social bricoleurs perceive and act upon opportunities to address local social needs. They are motivated by lived experiences and know how to address social problems. However, while Social bricoleurs have the lived experiences and knowledge to address social issues, the barriers consist of capacity and resources. Social bricoleurs are typically charities requiring financial capital and rely on top-down government support. Providing resources and capacity exists in the state. I have zero quarrels about this social policy/typology. Fundamentally, the resources and capacity do not exist. Levels of poverty and SCOPE’s call to action show evidence enough. Additionally, I would suggest two things. One. The current political framework of the Scottish political system is based on the Social bricoleur typology. Therefore, funding is allocated to charities/social enterprises that can mitigate social problems over the short term—providing the Scottish government with outcomes that support the national performance framework. Two. Social bricoleur thinking resulted in A-LEAF not receiving funding from the Scottish government’s social enterprise funding body. The Scottish Government’s refusal to fund A-LEAF lowers my subjective well-being as funding refusal has resulted in my continuing quest for a professional identity.

For readers unaware, the Scottish national performance framework is effectively the United Nations sustainable development goals (UN SDGs) as applied to Scotland. The nugatory differentials between the UN SDGs and the Scottish national performance framework are significant enough to propel A-LEAF into the typology of social constructionists – social constructionists build and operate alternative structures to provide goods and services addressing social needs that governments, agencies, and businesses cannot.

Iain and I had not advocated for a dramatic system change with the A-LEAF framework. Our request was merely to empower citizens and support the Scottish government’s social policy. The chapter has attempted to inform the readers of my subjective understanding of the operation of the Scottish political system, how the political system results in disabled people facing vast inequalities, and how Social bricoleur thinking provides possible barriers to necessary required system changes. The remainder of the chapter will spotlight the A-LEAF framework.

The fundamental theory of the A-LEAF framework is that a community’s collective well-being is empowered when citizens have a personal and professional identity that provides subjective well-being and simultaneously provides the person/self with good mental health. However, there is a direct correlation between personal and professional identity, social policy, and social norms. The workplace, the community, and government policy act as a tripod that supports citizens’ subjective well-being and provides good mental health. Absences of employment, paid or unpaid, reduces subjective well-being. Prohibition of the right to live in the community lowers subjective well-being. The perception that the government is not listening reduces citizens’ hope. As a society, we must ensure that citizens in our communities are provided opportunities to live well.

In the third sector, there is a focus on ‘self-management’. Self-management is an elongation that prolongs the required change. It is a mitigation method used to mitigate the effects of an ill-run society. I recognise that communities within communities can also empower citizens and foster the idea of citizenship. The problem, however, is that “a rising tide lifts all the boats” only when the focus is on the little boats.

Part one of the A-LEAF framework shows that citizens’ well-being correlates with each side of the tripod. The second part discusses what unites every citizen: waste. Rich, poor, disabled, and non-disabled, every citizen, every household, every institution, and every state produces waste. How do you turn waste into a monetisation opportunity which empowers citizens? Run the four Rs of the circular economy in reverse. Instead of reducing, reuse, recycle, and remove. Society should focus on recycling, reusing, reducing, and removing. Waste has a value that can be monetised. Plastic, glass, metals, and fabrics can all be recycled. The fantastic part of recycling is that a community recycling project has the potential to unite and empower every citizen. Within every action field/network within a society, an organisation will have a competitive advantage in recycling. Providing people and the planet are prioritised over profits. The organisation offers the strategic action field/community with a common good.

Part one: step two envisioned the possible collaboration opportunities that could empower citizens with subjective well-being. To prevent repetition, I will forgo the literary details. The graphic is provided in the chapter notes.

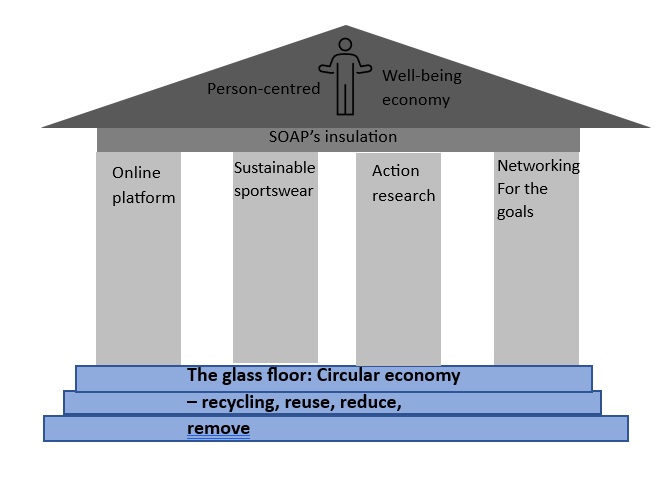

The final framework Iain and I designed before dropping the idea of A-LEAF as a social enterprise in 2023 was the House of Well-being. The House of Well-being is based on the Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland’s House of Care. The graphic I used, however, looks more like the US House of Representatives. That was either due to studying American-Russian international relations or watching too many American political TV shows. The House of Well-being/ A-LEAF framework for the well-being circular economy is as follows: The stairs metaphorically represent the circular economy but in reverse. The framework focuses on recycling as a monetary policy for community wealth building. From left to right, the four pillars are: (1) Build an online platform for keeping goods in the community longer, preventing goods within their life cycle from ending in landfills. (2) Within the community, there should be a focus on reducing polyester clothing for gym wear. Polyester, when washed, produces microplastics. The effects microplastics have on the environment are well known. The impact of microplastics on human life requires further investigation. (3) The action field/network should prioritise action research with all stakeholders in the field/community. This would reduce the requirement for lived experience boards, which, from my experience, reduces well-being. (4) Network for the UN SDGs goals. Every node/organisation with a network operating within the field should focus on achieving one or more of the seventeen sustainable development goals. The field the framework proposes is more robust than anything currently in place in Scotland. The nodes within the fields work towards the same strategy on a page (SOAP). Each field, of which there could be numerous in a geographical location, could adapt its SOAP to achieve the outcome of the field while working towards meeting the UN SDGs. The SOAP’s key performance and business growth indicators, designed to achieve the SDGs, can then be linked to the National Performance Framework. Directly connecting the strategic action fields back to the Scottish Government’s social policy agenda and simultaneously creating a database of community assets. Implementing the A-LEAF framework would create a person-centred well-being economy.

A-LEAF started with the idea that citizenship well-being is dependent on three areas. 1. Professional identity—without a sense of belonging and meaningful employment, well-being will remain low. 2. legislation. Government policy must support citizens in working on their own well-being. 3. Social norms of the community must support collaboration between citizens to develop a strong community.

To achieve the societal triangle, it was clear that the projects’ funding must be commercial. Removing community waste, upscaling, reusing, or recycling the community would generate a community wealth fund. Other commercial social enterprises could use the funds to develop projects that would empower citizen in their local community.

The circular image of well-being represents what Ian and I thought provided the best opportunities. Other projects are encouraged.

The House of Well-being was our last attempt to convince the funding bodies that A-LEAF, along with our Scottish government colleagues, had a solid plan for developing a well-being circular economy.