Introduction

Sunshine and rainbows, life is not. I was diagnosed with medulloblastoma at age four and live with the long-term condition resulting from the brain tumour- sight and hearing limitations, balance problems, and dyslexia-like issues as a child. Sunshine and rainbows are more challenging to find. Difficulties multiplied by the medical model, which said I had five years to live. The medical model said I was dead at ten. As of May 7th, I am forty years old. According to the medical model, I should not have attended high school. I have two undergraduate degrees and a master’s in social innovation and have worked since I was seventeen. I have volunteered in the Scottish third sector for ten years and have been a member of a UK political party since 2007—the relevance of my lived experience.

Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

(World Health Organisation Constitution)

The absence of disease or infirmity does not necessarily result in complete physical, mental, and social well-being. Replacing the medical model with the social model of disability via Human Rights (integration) (Scotland) Act 2026 would go some way toward achieving the World Health Organisation’s constitution in Scotland.

The Scottish National Action Plan for Advancing Human Rights II (SANP2) is the most recent publication available in the public domain. This article is a loose response to SNAP2 and recommendations for advancing human rights in Scotland.

The article is structured as follows. In the subjectivity section, I provided my opinion on SNAP2’s timeliness. In 2022 The Scottish Government had three boards- lived experience- advisory- executive providing evidence on human rights issues in Scotland. The board(s) evidence was not included in the SANP2 document. In the objectivity section, I take a more evidence-based approach to evaluate SNAP2- the evidence I use was sourced from online accessible websites and open-source research where possible. In the discussion section, I discuss human rights in Scotland, attempting to bring the subjective and objective areas together. Finally, in the recommendations section, I provide three recommendations which I see as a priority for advancing human rights in Scotland.

Subjectively, SNAP2 needs work.

Subjectively, the Scottish National Action Plan for Advancing Human Rights II (SANP2) is a missed opportunity. Equivalent to a tick-box bureaucratic institutional framework. Far from the radical reform, its pre-publication hype advocated. Disclosure. As a Social Innovation MSc graduate with over ten years of knowledge of the third sector and fifteen years of knowledge of political institutions in Scotland, I subjectively claim, after a second reading of SANP2, that SANP2 is a significant missed opportunity. I swear two things by subjectively applying lived experience to my initial review. One SANP2 is a bureaucratic document designed to give people with lived experience a perceived voice. Two SANP2 is the Scottish Government box ticking to confirm which previous records have been previously established.

Subjectively SANP2 needs to live up to the expectation of the pedestal on which it was placed. It is not easy to be objective when lived experience requires subjectivity. However, the next section will objectively cross-examine my subjectivity for this review’s legitimacy. What, though, are the bases of my subjectivity?

Webster (2022, p. 3) accurately points out.

“The 2021 report of the National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership recommended a new legal framework that will bring into [Scots Law] a range of internationally recognised Human Rights.”

We know that the Scottish Government plans to incorporate the UN Human Rights conventions into Scots Law by the end of the parliamentary session. Therefore, an objective revaluation of my subjective conclusion shall be on that cornerstone. Subjectivity based on lived experience, however, is not void of objectivity. Objectivity is subjectivity with a past dependency and place matters lens- see conversation section.

Dr Elaine Webster’s research paper’s theory/research is that communication around Human Rights can be given legitimacy by the bottom-up- rights holders when communication focuses on Human Dignity, not human rights.

To test Dr Elaine Webster’s theory, it is critical to identify the number of times the word ‘dignity’ is used in the SNAP2 document. And in which contents.

Three. Three times. The word “DIGNITY” was directly used three times in the SNAP2 document.

One direct reference to dignity is a quote from acritical 1 of the UN conventions “All Human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” (SANP, p.16).

All Human beings are free and equal in dignity and rights? Debatable. What is not debatable is that not all human beings remain free and equal in dignity and rights.

“In France, 57% of [woman’s] work is unpaid compared to 38% of men’s… all this extra work is affecting women’s health” (Perez, loc. 1461).

Where is dignity for women?

The fact is that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights dates to 1948. It is outdated. Article 16.1 reads.

Men and Women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and have a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during and at its dissolution”.

As Caroline Perez points out in the book Invisible Women. Women and men do not have the same right in marriage. The fact is that women and men do not have the same rights in society.

Not only is incorporating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights into Scots law, without a contemporary analysis of the wording, a direct violation of human dignity and added cost to the NHS. It is a violation of ethics.

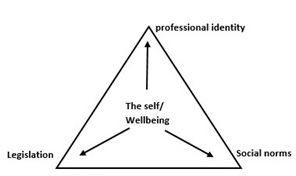

Since graduating with an MSc in Social Innovation from Glasgow Caledonian University, I have been in the process of setting up a community empowerment-action research network- A-LEAF Community Empowerment LTD. Figure 1 is my subjective interpretation of an objective fact.

Figure 1: Societal Triangle.

In project management, time, cost, and quality directly affect the project’s scope. My subjective view is that societal institutions can manage the health/well-being of individuals/ communities.

SNAP2 focuses on legislation exclusively, failing to consider how the perception of ones standing in society can affect health, well-being, and mental health. Moreover, as Perez points out, social norms-past dependency can hurt individuals and communities.

SNAP2 an objective view

The section on subjectivity shows how lived experience can influence an outcome. This section looks objectively at what SANP2 looks to achieve. Moreover, is the desired result attainable?

SNAP2: Scotland’s Second National Human Rights Action Plan. The key word is National. If the Human Rights Integration (Scotland) Act 2026 is to be implemented within all thirty-two local authority areas, with a minimum standard, then there should be an act of parliament. Moreover, the unofficial second chamber, the third sector interface, should support parliament. Given that SNAP2 was written by employees working in the third sector and supported by the general public. I can see no objective argument against SNAP2 as the most efficient, timely option for producing an open-source document to inform the people on the developments of their rights as rights holders.

Furthermore, SANP2’s principles, advancing human dignity, comply with Article 1 of the UN Convention on Human Rights. It also follows the Scottish Government’s communication about Health, Social Care, and other areas where duty-bearers have a particular obligation or responsibility to respect, promote and realise human rights. Moreover, SANP2 also interlinks with academic thinking. Therefore, there are no grounds for an objective point of reference.

Integration of the UN Convention on Human Rights comes in two parts. Part one: International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Part two: International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

This review shall focus predominantly on ICESCR. World Health Organisation (WHO) Constitution states

“Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

As ICESCR covers conditions at work, poverty, housing, social care, access to healthcare, and cultural life, the infringement of one or multiple of these areas would result in the mitigation of WHO’s constitution and border on a breach of Human Rights.

SNAP2’s purpose is in three parts:

- Carry out coordinated human rights activity by public bodies, civil society and rights holders.

- Promote greater awareness of human rights.

- Advance the realisation of human rights.

Objectively does SNAP2 do enough to identify and develop human rights in Scotland? Let us first consider what ICESCR requires—starting with work—decent work [is paramount] in realising the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. (Yunus Centre, 2023)

Workers’ rights are reserved for Westminster. Therefore, it would make little sense for public bodies or civil society to carry out coordinated human rights activity into workers’ rights.

In the discussion section, I discuss promoting and advancing human rights around worker rights.

- 24 per cent of children in Scotland are living in poverty.

- 69 per cent of children living in poverty in Scotland are in households where someone works.

- 38 per cent of children in lone-parent households live in poverty.

- 29 per cent of children with a disabled family member are in poverty.

(Child poverty action group, 2023)

Public bodies, civil society and rights holders must collaborate to identify where a child is living in poverty, identify the cause, and, where possible, mitigate the causes. Worker’s rights and gender pay gaps are reserved matters. However, evidence would support the need to push for human rights intervention regarding poverty.

Work and poverty (somewhat) are reserved for Westminster. As such, any attempt by the devolved public bodies or civil society to introduce a human rights approach could be limited. See the discussion section.

Housing, social care, access to healthcare, and cultural life are all devolved matters. Financial capital is the only obstacle to achieving a human rights-based approach in these four areas.

The Scottish budget is constrained via the devolved settlement. On this ground, SNAP2 can be objectively criticised as being a missed opportunity.

The Homelessness in Scotland 2021-2022 report highlights that 27,571 families were homeless; these households contained 42,149 people, 30,345 adults and 11,804 children. (Scot Gov, 2021). Additionally, the BBC puts the number of displaced people cases in Scotland at 28,944 in September 2022 (Clements, 2023).

These figures are alarming. What is more problematic, though, is that in 2022, the cost estimation for a house is anywhere between £1,750 and £3,000 per m2 (Bahar, 2023). The average new three-bedroom home in the UK is 88 m2 (Joyce, 2011). The Scottish government must therefore find £7,641,216,000; £3000 x 88m2 x 28,944 cases. Supposing it aims to avoid legal issues. See the discussion section.

Quantifying a reasonable estimate of the cost required to build 28,944 homes in Scotland is possible. Quantifying the cost of raising social care to a human rights standard is more complex. Care Information Scotland (2022) states that councils will pay £832.10 per nursing per resident in respect—or £719.50 for residents in residential care. Public Health Scotland (2022) says there are estimated to be 33,352 Scots over 18 living in care homes. Based on the lower £719.50 figure, the Scottish Government is paying a minimum of £23,996,764 per year in social care costs.

Pause. The figures quoted above are an estimate. They are intended to provide an objective validation to the argument that SNAP2 could have offered additional recommendations on how a human rights-based approach to housing and social care could be achieved.

The Public Bodies (joint working) (Scotland) Act 2014 was intended to integrate the NHS and Social Care nationally. Colleagues at the Alliance shall remember a year of work which provided the people-powered health and well-being reference group on objective reflection- all of whom had long-term conditions or were unpaid carers with a little well-being/ confidence boost. However, as Millar et al. (2020) point out:

“…for those participants with conditions that require consistency and stability. The short-term and transitory nature of the project also creates difficulties in assessing [lived experienced programmes] effectiveness over time – a challenge shared by those working on music and well-being projects in non-formal settings more generally.”

The people-powered health and well-being reference group was not a music well-being project. The point I am arguing is the short-term and transitory nature of lived experience boards. As Millar et al. (2020) say.

“We question, therefore, what happens with project participants, including beneficiaries and those running a project, when ‘the light goes off’, and the task terminates.”

Burnout is not only a problem for project participants, including beneficiaries and those running a project. Burnout is a significant issue for the NHS. As Nicholson (2023) states, the current state of the HNS is a ‘Ticking Time Bomb’. Stress, anxiety and burnout are pushing employees out of the health service. The media blames COVID-19 for this. The fact is that this is a gender data gap problem.

“A 2011 analysis of the data collected on British civil servants between 1997 and 2004 found that working more than fifty-five hours per week significantly increased women’s risk of developing depression and anxiety- but did not have a statistically significant impact on men”.

(Perez, 2019, loc. 8961)

As Caroline Criado Perez says in her book invisible women, “A husband creates an extra seven hours of housework a week for women… regardless of their employment status” (Perez, 2019, loc. 8961)

Any Scottish Government budget after 2026 must have a gendered lens to achieve a human rights-based approach.

This section has provided objective-quantitative evidence that supports the initial argument- SNAP2 is a missed opportunity. However, as said in the subjective segment, objectivity is not straightforward when lived experience enforces subjectivity.

As a member of the Alliance, Inclusion Scotland, and Glasgow Disability Alliance- a holder of an undergraduate degree in politics, philosophy, and economics- and an MSc in Social Innovation, SNAP2 is a subjective missed opportunity- the objective evidence confirms why I am frustrated with the SANP2 document. However, rights holders all have personal viewpoints- If SANP2 archives the objective of a human rights social marketing campaign, then I will accept that my original argument was too harsh.

Discussion

Article 27 of the UN Universal decoration of human rights says.

- Everyone has the right to freely participate in the community’s cultural life, enjoy the arts and share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

- Everyone has the right to protect the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.

Cultural rights should have been included in the objective evidence section- I, however, needed more objective and subjective knowledge in this area. SNAP2 asks for the realisation of a human rights culture. What, though, does that imply?

Point 2 is not relevant; intellectual property rights are covered in UK law.

The key word in point one is “community”. More research into the diversity, inclusion, and belonging model is required to achieve the desired outcome. Scottish communities are diverse. However, is there a sense of inclusion and belonging? More academic and action research is needed in this area.

Focusing research on poverty and employment rights as it relates to cultural rights could enhance the sense of belonging for citizens living in Scotland.

The working of people-powered health and well-being reference groups could be used as a framework for civil society to carry out action research.

The overall question could be: Does working locally benefit people, the planet and the community? While at the same time contributing to a subjective well-being premium?

Academically that question could be adapted to fit numerous social science studies. Looking back on Article 27, a collaborative action research project supports scientific advancement and its benefits for the community. Scotland, in this case.

Past dependency and place matters. An academic phrase meaning contemporary life today is shaped by past policy decisions. Integration of the UN conventions on human rights is about the culture and legacy this generation passes to the next. A heritage that is constrained by the devolution settlement. The Human Rights (integration) (Scotland) Act 2026 is possible with devolution. However, poverty could be mitigated more effectively with the full powers of an independent state. Montgomery and Baglioni published the report The Gig Economy and its Implications for Social Dialogue and Workers’ Protection in 2020. This report targets the UK, as employment law is a reserved matter. Reserved, devolved issues will impact the wording of The Human Rights (integration) (Scotland) Act 2026. The reason for including accumulated devolved problems in a review of SNAP2 is that it is misleading not to address this issue before The Human Rights (integration) (Scotland) goes to the public conversation stage.

SNAP2 is not The Human Rights (integration) (Scotland) bill; perhaps the criticism is too harsh. SNAP2 is the last document before the public conversation, highlighting the problems of devolution and human rights that are paramount, dissevering more than a footnote.

The topic of Housing and Social Care is devolved. Furthermore, they are topical. Moreover, therefore, likely to dominate the public conversation on human rights. My calculations estimate that the Scottish government will be required to find £7,641,216,000 to build 28,944 new homes between now and 2026. 28,944 are the number of cases of homelessness in Scotland (Clements, 2023). However, it is not as simple as building 28,944 new homes at the cost of £7,641,216,00. Remember, WHO’s constitution states.

Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

Therefore, building 28,944 new homes would require other community actors, schools/nurseries, sports clubs, shops, accessible transport, pubs/ social activities—and work. Forty-two thousand one hundred forty-nine people, 30,345 adults and 11,804 children (Scot Gov, 2021), are homeless in Scotland. To prevent repeating the mistakes of the past- housing estates. Integration of the UN Convention on Human Rights must consider the discourse of equal opportunities. The argument for consideration to the Human Rights (integration) (Scotland) bill writing team is that a gender budgeting approach would go some way to addressing barriers to opportunities for other groups in society too.

The purpose of the discussion section was to engage the reader in a thought-provoking extension of the subjective and objective areas. My conclusion was that SNAP2 was a missed opportunity. I base that premise on lived experience- as pointed out in the subjective section. My premise in the objective section is that the objective quantitative data confirms the subjective belief.

Conclusion- premise. The bases of a philosophical argument.

Socrates has two legs.

The man has two legs.

Socrates, therefore, is a man.

My political philosophy is that society needs a large enough state to provide citizens with a quality of life that is equal to WHO’s constitution. That said, with the limited powers of the Scottish parliament, Scotland needs an intelligent state, not just a large state.

Recommendations

Inspiration for this paper is the lack of actionable items that can be actioned now to advance human rights in Scotland. In this section, I provide three things that could be written into Scots law today. The first should come as no surprise. Insert into the Human Rights (integration) (Scotland) Act 2026:

- The social model of disability should replace the medical model.

- the social model of disability is required to achieve human dignity for all citizens.

- Human dignity is required to achieve a human rights-based approach. Furthermore, dignity is required to align the Scottish NHS with the World Health Organisation’s constitution.

The second recommendation should come as no surprise either. In 2019 male drivers in England outnumbered female drivers by 9 per cent (Statista, n/d). However, 82.2% of employees [in the care sector] were women, and only 17.8% were men [2018] (Shepherd, 2018).

- Transport in Scotland should be designed with a gendered lens.

2.1 the lack of timely, accessible transport prevents care workers from promptly coming to clients’ homes.

2.2 Further research is required to identify if the lack of timely accessible transport prevents care paid or unpaid from timely transport, adding additional working hours to their day, which adds to health issues.

The last recommendation focuses on the role of social enterprises in Scotland. Human rights are for all citizens living in Scotland (and internationally). To achieve a human rights-based approach in Scotland, a top-down approach to human rights is required. However, a bottom-up approach can identify and mitigate local issues quicker than a top-down approach. Therefore, the Human Rights (integration) (Scotland) Act 2026 should insert.

- The role of social enterprise is essential in securing a human rights approach in Scotland.

3.1 The Scottish Parliament will oversee the setting up a Scottish Social Enterprise mark.

3.2 Social Enterprises in Scotland will report directly via a Scottish Parliamentary committee.

3.2.1 Reports to the parliamentary committee will include business growth indicators and key performance indicators- directly linked to UN Sustainable Development Goals.

3.3 The role of the national and regional social enterprise networks shall continue to provide support to social enterprises.

Social Enterprise (SE) is a new concept for most- as SE has no set definition, it isn’t easy to understand. In Scotland, the Scottish Government has set the framework for SE to mirror the charitable- third sector- this framework is too limited and reinforces the top-down governmental approach. Nor is SE the fourth sector- the third sector plus is the best way I would frame a definition of SE in Scotland. As Ehrlichman (2021, p. 18) states

“Society can[not] let networks form according to existing social, political, and economic patterns, which will likely leave us with more of the same inequities and destructive behaviours”.

SE offers an opportunity to deliberately and strategically catalyse new networks to transform the systems we live and work in. What does SNAP2 ask the Scottish Government to do?

- Carry out coordinated human rights activity by public bodies, civil society and rights holders.

- Promote greater awareness of human rights.

- Advance the realisation of human rights.

A system change via active action networks (research) provides that opportunity.

Conclusion

The Human Rights (integration) (Scotland) Act 2026 and the support documents available to the public as of summer 2023 provide an opportunity for a national conversation on human rights in Scotland and internationally. The purpose of this article is threefold. This article indirectly addresses the Sottish National Action Plan on Human Rights document. However, this article does more than address SNAP2. This article provides a personal evaluation of why SNAP2 is a missed opportunity. However, subjectivity is not absent from objectivity—every unique viewpoint this article claims is supported with objective evidence.

SNAP2 is a missed opportunity. My subjective lived experience is the ground for that thinking. However, I have never, to this date, let my childhood medulloblastoma or long-term conditions define me. I have no intention of starting now. As I said in the objective section, the SANP2 document provides a timely transition towards the upcoming Human Rights (integration) (Scotland) Bill.

The second reason for writing this paper, my time on the Scottish Government’s lived experience human rights board was insightful. I have taken many of the points to heart and shall embed them into A-LEAF moving forward. However, this article is the written evidence I could not say to fellow board members.

The final reason for writing this paper is to use my lived experience, my academic experience and my human capital experience of the third sector in Scotland to add additional information to the human rights conversation in Scotland. I hope I have achieved that outcome. My last thought is that many social enterprises are doing exciting things in Scotland. The Scottish Government and third-sector interfaces should include social enterprise experience moving forward.

References

Bahar, U, (2023) ‘How much does it cost to build a house?[2023 £/m2 building prices], ‘Urbanist Architecture’ [online] Available at How Much Does It Cost to Build a House? [2023 £/m2 Building Prices] – Urbanist Architecture – Small Architecture Company London

(Assessed 19/04/2023)

Care Information Scotland (2022) ‘ Standard rates ’, ‘Care Information Scotland’, 14 April [online] Available at Standard rates | Care Information Scotland (careinfoscotland.scot)

(Assessed 19/04/2023

Clements, C (2023) ‘Homelessness rases to the highest level on record’, ‘BBC’, 31 January [online] Available at Homelessness rises to highest level on record – BBC News

(Assessed 19/04/2023

Ehrlichman, D (2021) ‘impact networks’, Oakland CA, Berret-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Glasgow Caledonian University, (n/d) ‘GIG: The Gig Ecomony’, ‘Yunus Centre for social business and health ’, n/d [online] Available at GiG: The Gig Economy | Glasgow Caledonian University | Scotland, UK (gcu.ac.uk)

(Assessed 19/04/2023)

Joyce, J ,(2011) ‘Shoebox homes become UK norm’, ‘BBC’, 14 September [online] Available at ‘Shoebox homes’ become the UK norm – BBC News

(Assessed 19/04/2023)

Millar, SR, Steiner, A, Caló, F & Teasdale, S 2020, ‘COOL Music: a ‘bottom-up’ music intervention for hard-to-reach young people in Scotland’, British Journal of Music Education, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 87-98. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051719000226

Nicholson, K, (2023) ‘ Ticking Time Bomb- here’s how many NHS staff actually want to quit’, ‘Huffpost’, 29 March [online] Available at Here’s How Many NHS Staff Actually Want To Quit | HuffPost UK Life (huffingtonpost.co.uk)

(Assessed 19/04/2023

Perez, C, C, (2019) ‘Invisible Women Exposing Data Bise in a World Designed for Men’. London: Vintage.

Scottish Government, (2021) ‘Homelessness in Scotland:2020 2021’, ‘The Scottish government’, 29 June [online] Available at The Extent of Homelessness in Scotland – Homelessness in Scotland: 2020 to 2021 – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

(Assessed 19/04/2023)

Shepherd, W, (2018) ‘Gender imbalance in the social care sector: time to plug the gap ’, ‘HRZone’, 31 May [online] Available at Gender imbalance in the social care sector: time to plug the gap | HRZone

(Assessed 19/04/2023)

Statista, (2022) ‘Share of full car driving license holders among all adults in England between 1975/1976 and 2019, by gender ’, ‘Statista’, 20 April [online] Available at Adults holding driving licenses in England 1975-2019 Statistic | Statista

(Assessed 19/04//2023)